The River Thames is a river that flows through southern England, including London. It is the longest river in England; it is also the second-longest river in the United Kingdom at a whopping 215 miles long. The River Thames flows through Oxford, but this stretch of the river is called the Isis. It would have been a bustling place in those days, and like the beaches of yesterday, the Thames would also have been a place where people discarded items they no longer wanted, so you never know what you might find there.

People have been beachcombing on the Thames since the latter part of the 18th century as a way to make some extra money. These days, people go to beaches and rivers like the Thames in search of items to collect as a hobby , and it’s becoming increasingly popular.

What to expect from our article

What is a mudlark?

If you go mudlarking, you are a mudlark. A mudlark is someone who scavenges in the mud by a river, searching for valuable items to sell. The term “mudlark” was used to describe people who scavenged the river during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Mudlarking is still as popular now as it was then, and people travel far and wide for a chance to search the Thames for lost treasures.

History of the Thames

The River Thames has played an essential role in human history and has been used for many things, including;

- Economic resources

- Maritime routes

- Boundaries

- Freshwater and food sources

There is evidence of human habitation along the river dating back as far as Neolithic times; in fact, the British Museum holds a decorated bowl found in the river at Hedsor in Buckinghamshire dating back to 3300–2700 BC. It is thought that there may even be artefacts buried beneath that date even further back, but we will never know as they are buried in tons of silt that has collected over time.

Evidence dating back to Pre-Roman Britain is visible at many locations along the river. These include;

- Navigations

- Bridges

- Watermills

- Prehistoric burial mounds

Rivers were an essential factor when deciding to build a castle. Many of the castles you see in Britain were constructed on or near the river. Castles came under siege a lot, and some of those sieges lasted for months at a time. The river would literally be a matter of life or death if you were under siege. You could use the river as a means of escape or to transport food and drink into the castle. The Thames was cemented in history in 1215 AD when King John was forced to sign the Magna Carta at Runnymede.

Dumping ground

As early as the 1300s, the Thames was used as a dumping ground, turning the river into an open sewer. In 1357, Edward III described the state of the river;

“Dung and other filth had accumulated in divers places upon the banks of the river, with fumes and other abominable stenches arising therefrom.”

By the 18th century, the Thames would become one of the world’s busiest waterways. The population of London was growing at a tremendous speed, increasing the amount of waste that entered the river. It was used to dump many things, including

- Human excrement

- Waste from slaughterhouses, fish markets, and tanneries

- Manufacturing and household waste

Between 1832 and 1865, cholera was rife with outbreaks that killed tens of thousands of people. In 1858, a time known as the Great Stink, the pollution in the river became so bad that sittings at the House of Commons had to be abandoned. They hung drapes soaked with chlorine in an attempt to disguise the smell of the river, but it didn’t work. A decision was made to clean up the river, and massive sewer systems were constructed.

You can imagine it would have been pretty grim mudlarking on the Thames back in those days, but these were times when people were desperate, and desperate times called for desperate measures if you wanted to avoid being sent to the poor house.

What is the difference between mudlarking and beachcombing?

- The most straightforward answer is that beachcombing is done on the beach, and mudlarking is done on a river. Mudlarking can be a mucky experience because you usually retrieve items from the mud, whereas beachcombing items are typically covered in sand.

- Beachcombed things tend to be smooth from being tumbled around in the sea, whereas mudlarked items are usually in the same place from when they were dropped, buried in the mud.

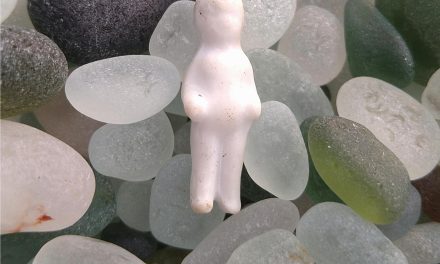

- If you have a fast-moving river, you might find river glass that looks similar to beach glass; it may be smooth and rounded, but there are clear differences between them. Beach glass is usually clean, but river glass is typically green with algae.

- You are likely to find undamaged items while mudlarking, whereas on the beach, you tend to find fragments. However, if you are lucky enough to find a coastal rubbish dump, you may be lucky and find lots of intact things like bottles, jars, and even jewellery.

What do you need to go mudlarking?

There are a few things you will need to go mudlarking.

- Wellies or sensible footwear

- Bag for your muddy shoes

- Gloves

- Finds bag

- Wet wipes and hand sanitiser

- mobile phone.

- Tide app or tide table

- Permit

Health and safety

Footwear– you should wear sensible footwear when mudlarking; you never know what might be lurking beneath the surface, and the last thing you want to do is end your search with a trip to A&E.

Gloves – you must wear gloves while mudlarking on the Thames; the sewage systems that were put in place during Victorian times are not equipped to handle modern-day living, so they overflow from time to time, which means there is raw sewage on the Thames and you do not want that on your hands.

You need to be aware of something else when mudlarking on the Thames, and that’s Weil’s disease. Weil’s disease is spread by rats’ urine in the water. Infection is usually contracted through cuts in the skin, the eyes, mouth, or nose. Flu-like symptoms include

- Temperature

- Aching muscles

- Aching joints

If you experience any of these symptoms after visiting the Thames, you should seek medical advice immediately.

Permits and restrictions

If you want to go for a wander on the Thames, you can do so freely, but if you intend to go mudlarking, then you will need to purchase a permit. Permits are charged daily, or if you want to be a regular visitor, you can buy a yearly permit. The cost of the permit is per person, which can be expensive, but think of all of that history just sitting there waiting to be discovered. There are parts of the Thames that are off-limits, so be sure to check before you purchase. Click here for more information on permits and restrictions.

Can I metal detect on the Thames?

Yes, you can go metal detecting on the Thames, but remember that scraping the surface with any type of tool is considered digging and for this, you will need a permit. All the foreshore in the UK is owned by someone; the PLA and the Crown Estate are the largest landowners of the Thames foreshore and jointly administer permits that allow metal detecting and digging. Metal detecting is not a public right, so you will need to seek permission from the landowner on any land you wish to detect, including the Thames.

Reporting significant finds

You must report any objects that could be of archaeological interest to the portable antiquities scheme. The portable antiquities scheme records all of the archaeological discoveries made by the public in England and Wales. The Treasure Act code of practice contains a directory of coroners in the Thames area.

If you believe that a find may qualify as treasure, then you should contact the coroner for the district in which the object was found; you should do this within fourteen days of making the find. You can also contact the finds Liaison Officer at the Museum of London on 0207 814 5733. The finds liaison officer will advise on what to do next.

It is essential to report historical finds as they could lead to critical historical discoveries that we never knew existed. Your find might even change the course of history!

Full advice on the portable antiquities scheme can be found here.

The full version of the Treasure Act 1996 can be found here.