This article will give lots of information about the buildings at the Weald & Downland Living Museum. Travel with us through history as we explore the grounds and historic buildings situated here, helping to tell the story of the people who may have lived and worked in them.

The Weald & Downland Living Museum is an outdoor living museum situated in the South Downs National Park. The museum was originally called Weald & Downland Open Air Museum, but it changed its name in 2017. It was founded by a small group of enthusiasts led by the late Dr. J.R. Armstrong (MBE). The main goal was to create a place where historical buildings could be relocated. Each structure was meticulously recorded, dismantled, and rebuilt at the museum as it would have been in its original location.

Weald & Downland try to preserve the buildings at their original locations; however, this isn’t always possible. The buildings are only relocated to the museum when all options have been exhausted. We are fortunate to have projects like this one; otherwise, all of the buildings at this site would have been demolished, and their history would have been lost forever.

Weald & Downland Living Museum is fairly similar to St Fagans National Museum of History, which is located in South Wales. St Fagans is also a living museum and is situated in the 100-acre gardens of St Fagans Castle. If you haven’t been before, you really should check it out.

What to expect from our article

- 0.1 What can you see at the Weald & Downland Living Museum?

- 0.2 Weald & Downland Living Museum Cafe

- 0.3 Weald & Downland Living Museum galleries

- 0.4 Medieval House from North Cray

- 0.5 Upper Hall from Crawley

- 0.6 Painted panels Fittleworth

- 0.7 Market hall from Titchfield

- 0.8 Medieval Shop from Horsham

- 0.9 House from Walderton

- 0.10 Building from Lavant

- 0.11 House Extension from Reigate

- 0.12 School from West wittering

- 0.13 Medieval House from Sole Street

- 0.14 Poplar Cottage from Washington

- 0.15 Gonville Cottage from West Dean

- 0.16 Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen from Sundridge

- 0.17 Cattle Sheds from Sussex

- 0.18 Wagon Shed from Wiston

- 0.19 May Day Farm Barn and Stable from Tonbridge

- 0.20 Hay Barn from Ockley

- 0.21 Barn from Cowfold

- 0.22 Bayleaf Farmstead from Chiddingstone

- 0.23 Hall House from Boarhunt

- 0.24 Medieval Building from Hangleton

- 0.25 Anglo Saxon Hall House

- 0.26 Downland Gridshell

- 0.27 Treadwheel from Catherington

- 0.28 Longport Farmhouse from Newington

- 0.29 Aisled barn from Hambrook

- 0.30 Pugmill House from Redford

- 0.31 Brick drying shed from Petersfield

- 0.32 Plumber’s workshop from Newick

- 0.33 Whittakers cottages from Ashtead

- 0.34 Bell Frame from Stoughton

- 0.35 Church from south Wonston

- 0.36 Horse whim and open shed from West Kingsdown

- 1 You may also like

What can you see at the Weald & Downland Living Museum?

There is so much to see at The Weald & Downland Living Museum, including houses, working buildings, period gardens, farm animals, walking trails, and a millpond. The buildings are spread over 40 acres, with each location representing a specific period.

There are nearly 1000 years of history within the homes, farmsteads, rural industries, and archaeological reconstructions at the museum. Some of the buildings at Weald & Downland are still in use today; two of those buildings are the bakery and the watermill. The flour produced by the watermill is used to make bread and cakes, which are sold on-site. You can also purchase the flour to take home and make your own bread and cakes.

Weald & Downland Living Museum Cafe

The cafe at Weald & Downland Living Museum overlooks the millpond and opens half an hour before the museum, which is handy as you can grab a drink or something to eat before you enter. There are two seating options available for the cafe: inside, which is dog-friendly, and outside, on the deck overlooking the pond. There is a variety of food available to purchase at the cafe, including hot and cold food, cakes, and ice cream. There are also gluten-free, vegetarian, or vegan options available.

Weald & Downland Living Museum galleries

After leaving the gift shop, you will walk through the interactive visitor centre, which contains historical exhibits related to rural and farming life. You can spend some time in this section learning about what it would have been like to be a farmer in the past. As you leave the visitor centre, you will immediately notice a cluster of buildings, the most prominent of which is the medieval house from North Cray.

Medieval House from North Cray

North Cray Medieval House was originally built in North Cray, Kent, during the 15th century. This house is a classic example of a medieval hall house. North cray is divided into four bays, with a central open hall in the middle. According to archaeological evidence, red paint was used to paint the timbers in the original construction of this house, which is why the timbers were painted red in the reconstruction.

Evidence shows that red paint was often used to paint the timbers in medieval buildings, some of which have survived in France and Germany to this day.

In 1968, the London Borough of Bexley intended to demolish this house to widen the road; however, it was decided that the building should be saved and relocated to the museum. The structure was dismantled, and the timbers were placed in a storage facility.

Ten years had passed with no sign of the building being re-erected at a new location, so the decision was made to donate the timbers to the Weald & Downland Living Museum instead. The medieval house sits perfectly among the other village buildings of this period.

North Cray Medieval House underwent extensive renovations during the 16th and 17th centuries. The final alterations that were carried out show the front of the building being used as a grocer’s shop, with the rest being divided into two small cottages. It was not unusual for buildings during this period to be multi-purpose, as you will see in some of the other buildings at this location.

The Medieval House from North Cray, Kent was dismantled in 1965 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1984.

Medieval House from North Cray

Upper Hall from Crawley

Crawley Upper Hall was originally located in Sussex. This building was situated behind a house on the east side of the town’s historic high street. The old barn as it was known had been in use as a storage shed for quite some time. Crawley New Town Commission originally intended to demolish this building, but after an extensive investigation, evidence of a much bigger building was discovered.

During the investigation of Crawley Upper Hall, It was discovered that the original building would have been much longer than the building still standing. It is thought that the upper floor may have contained a long hall that would have been used for some sort of public gathering. The ground floor was divided into separate bays, it’s possible these bays were used for storage or even as shops. Another possibility is that the structure was once part of an inn.

The reconstruction of the upper hall at Weald & Downland Living Museum shows how it would have looked with missing bays. Unfortunately, the door head in the front wall is not the original, however, the one in the reconstruction is based on a surviving example from a building in Crawley High Street which makes it a little more authentic.

Crawley upper hall sits in its current location to the left of North Cray Medieval House. It houses the Museum’s library and a meeting room and is closed to the public. Medieval buildings wouldn’t have had glazed windows, but To be able to use this building for its current purpose, the windows had to be glazed.

The Upper Hall from Crawley, Sussex was dismantled in 1972 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1978.

Upper Hall from Crawley

Painted panels Fittleworth

Just inside the entrance of the Crawley upper hall, you will see the Fittleworth painted panels. These panels were rescued from an upper room of Ivy House in Fittleworth in 1968.

The elaborate black-on-white floral designs are thought to date to around 1580-1600. The paintings were discovered during renovations, and It is thought they were covered up sometime around the 18th century. New plaster was applied to the walls during the renovations, however, it was placed on top of battens, which helped to preserve the paintings underneath. Evidence shows that the Fittleworth paintings would have been quite extensive at one point covering all four walls of the room, including the timbers. Sadly some of the paintings had been destroyed during earlier repairs when the wattle and daub panelling was replaced.

Ivy house was a listed building and documents show that permission was sought and granted to renovate the property. The paintings were not visible at the time and were only discovered after renovations had begun. The owner should have notified the authorities as soon as he found the paintings, but he was too interested in his renovations to care about them. Sadly before anyone was made aware of what was found he had already destroyed some of them and probably would have destroyed them all if he had his way. Once the museum was made aware of the paintings they were permitted by the owner to remove them.

Market hall from Titchfield

Titchfield Market Hall was built in its original location in Titchfield, Hampshire during the 16th century. Market halls like this one were once common throughout England and the majority of them were constructed with a timber frame. Market halls were used for many purposes, for the poor to sell their wares, a lock-up for offenders, and the private upper chamber probably would have been used for public meetings.

Many market halls were demolished during the 18th-19th century because they no longer served the purpose for which they were built. Many were replaced with more solid structures with enclosed rooms taking the place of the previous open arcade-style building. In many other cases, market halls were relocated to less desirable locations and left to decay.

Among the earliest surviving market halls are several that date from the 15th and 16th centuries. Two examples of these can be found not too far from the museum. The stone Market Cross in Chichester and the timber-framed Market Hall in Midhurst were constructed in the early 15-16th century.

The market cross in Chichester

The Market Cross is a grade I listed building and is also a scheduled monument under the Ancient Monument Areas Act 1979. It is believed to have been built in 1501 by Bishop Edward Story. The market cross does not have a chamber above it like other market halls and according to the Deed of Gift from Bishop Storey in 1501, the purpose of the covered arcade was for poor people who wish to sell their wares. The Cross was built on the site of an earlier wooden construction which had been erected by Bishop Rede in 1369-1385.

The Market Hall in Midhurst is a Grade II listed former 16th century Market Hall that has undergone extensive restoration with modern brick infill. The building used to extend further south, and the ground floor was once an open space that has since been enclosed. It now forms part of a hotel but like other market halls of its time, it was once used as a multipurpose building.

The Market Hall from Titchfield, Hampshire was dismantled in 1971 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1974.

Market Hall from Titchfield

Medieval Shop from Horsham

The original location of the Horsham Medieval Shop was number 11 Middle Street in Horsham. In 1967 the site where this shop was situated was scheduled for redevelopment, and the medieval timbers were saved and donated to the Museum in 1985. During dismantling it was discovered that the timbers were heavily coated in soot, indicating that open fires had been burning over an extended period within the property. A fire could have provided warmth to the occupant, but it is also possible they were using it to produce smoked meat, pies, or loaves of bread which they could then sell in the shop.

This building formed part of what was originally known as Butchers Row which would later become Middle Street. The shops on butcher’s row were likely built to replace the marketplace as the area expanded. Documentation shows that the last occupants of number 11 Middle Street were Robert Dyas, Ironmongers.

Much of the building’s history is unknown, but evidence suggests it dates back to the late 15th century. This building would have originally been divided into two semi-detached units one of which had exclusive access to the upper floor. It is presumed that the person in this unit was the owner and the upper floor served as his living quarters. This theory is based on the fact that the other unit did not have access to the stairs that led to the upper floor.

Each unit had an open-fronted shop with a display much like you would see in a modern butcher’s shop. Sadly none of the timbers survived from the original shop front so they are not exactly sure what it would have looked like. The reconstruction is based on a similarly aged shop that was located nearby. There wouldn’t have been any windows in medieval times so the front would have been closed off using large wooden shutters.

The Medieval Shop from Horsham, Sussex was dismantled in 1968 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1985.

Medieval Shop from Horsham

House from Walderton

This House from Walderton, Sussex dates from the early to the mid-17th century. It was donated to Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1979, as it was going to be demolished. One-half of the building had been empty since around 1930, and the interior walls had collapsed, rendering the building uninhabitable.

This house is a little deceiving because beneath the flint and brick exterior are the ruins of a medieval timber-framed structure with an open hall. The reconstruction of this house at Weald & Downland is based on modifications that were made to the house after the 17th century.

On the ground floor, at the east end, there is a living room with a room above it. Both of these rooms are equipped with fireplaces, and they are connected by a winding staircase.

The old open hall has been replaced by a room that was most likely the bakehouse because it contains a bake oven, the room above it is accessed via another staircase.

There are two storerooms on the west side of the house that are similar to that of a buttery and pantry.

The windows in this building were altered in the 18th and 19th centuries, but the window frame in the east end of the room was protected by an extension, so it survived in its entirety. As you can see, the bricks used have been roughly cut to size the frames were then plastered to finish them.

At this end of the house, in addition to the windows, were several other details that had been preserved exceptionally well. Excavations uncovered portions of the original 17th-century brick floor that had been covered up during earlier renovations, as well as the original door to the cupboard beneath the stairs. The reconstruction shows how the original brick floor looked when it was found.

Inspiration for dressing the interior of this house is taken from other traditional 17th-century houses. The two rooms at the east end were furnished based on the 1634 John Catchlove, goods and chattels inventory. It is believed that John Catchlove was the owner of the house during this period and the inventory shows a list of items that would have been in the house when he lived there.

To the rear of this property is a recreation of a 17th-century garden It would have been primarily used for the production of vegetables, fruits, herbs, and for keeping livestock. However, some plants, such as gillyflowers and irises, were grown for their aesthetic qualities. A wider variety of vegetables like cabbage and kale were also available during this period.

The House from Walderton, Sussex was dismantled in 1982 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1982.

House from Walderton

Building from Lavant

To the right of North Cray, Medieval House is the Lavant Building, its original location was Lavant, West Sussex and it was attached to the manor of Roughmere. It’s not clear what the intended use of this building was but researchers think it may have originally been built for a public purpose. It is thought the upper floor was being used as a courtroom or public meeting place and the lower rooms were used for storage.

It was thought that the Lavant building was constructed in 1773 as this date was inscribed on a stone block set on the front wall. However, it was soon discovered that this date is not the date the building was constructed. During the 18th century, there was a fire which destroyed the interior of the building, and it was probably during this time the date stone was added. From 1773 onwards the Lavant building was being used as a house with most of the original doorways and windows blocked up or altered during this time. It wasn’t until the building was dismantled in 1976 were these original features discovered.

The building from Lavant, Sussex was dismantled in 1976 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1978.

Building from Lavant

House Extension from Reigate

Behind the Lavant building is the Reigate House Extension. This building was originally added as an extension to the back of a mediaeval house at 43 High Street in the early 17th century. The extension was due to be demolished and replaced by a shopping centre In 1981, a decision was made to preserve it and it was donated to the museum instead.

The extension includes two main rooms on each floor, as well as a basement and attic. The basement walls and chimney were built with Reigate Stone, but the original stone had deteriorated so badly that only a small portion of it could be saved for use in the reconstruction. The extension was added to an earlier structure that was thought to be a late-medieval stair tower. The two main rooms were originally accessible via the old stair tower.

There are carved fireplaces in each of the rooms, and a small cupboard has been created in the corner of the lower room using oak panelling. There is also a cupboard under the stairs that leads to the attic in the upper room. The dismantling of the extension revealed the remains of beautiful decorative wall paintings that had been covered in several coats of paint; the majority of these paintings were discovered in the upper room. The walls were floral in design with a painting over the mantel featuring St George slaying the dragon.

A family of brewers named Cade lived at 43 High Street from 1587 to the mid-eighteenth century. When Walter Cade (who I assume was head of the house) died in 1621, the property was left to his three children and a grandchild, it’s possible that the extension was added to accommodate all of the family.

Unfortunately, the extension was closed during our visit so I don’t have any pictures of the interior, however, you can see the interior of the building here.

The House Extension from Reigate, Surrey was dismantled in 1981 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1987.

House Extension from Reigate

School from West wittering

The original building was a cartshed, it would have had a hipped roof and was open at one end. It is believed to have been built sometime around the 18th century and was converted into a school at the end of the 1820s.

The open end of the cart shed was filled in and gables were added to the roof. The new flint and brick walls were constructed with hard cement mortar and were given the characteristic raised pointing that you see today.

Plaster was used on the interior walls, which were lined to give the appearance of stone blocks. The floor was laid with stone slabs, and a chimney was constructed to accommodate a stove.

There was also a yard and a stable on the grounds of this property, the stable is now being used as a potting Shed by the museum’s gardening team.

Documents from 1830 show a yearly payment was being made to the parish from the Oliver Whitby trust to fund the education of six poor girls. Oliver Whitby was the son of a Chichester Archdeacon who left properties in his will for the creation of a charitable trust which focused on education. The trust went on to fund the new National School, which was built in 1851, and the old schoolhouse was abandoned. It was dismantled in 1981 as it was on the verge of collapse.

The Oliver Whitby trust also established the Bluecoat School, which was a twelve-boy boarding school in Chichester, it was founded in 1712 and continued until 1950.

The School from West wittering, Sussex was dismantled in 1981reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1984.

School from West wittering

Medieval House from Sole Street

This building was originally located in Sole Street in Kent and was built around the 15th century. It was declared unfit for human habitation in 1960, but it remained in use until 1967. Efforts were made to preserve this building at the original location however, that was not possible and a decision was made to move it to Weald & Downland Living Museum. A new visitor centre was planned for the museum and the medieval house was dismantled for a second time and re-erected in its current location in 2016.

This medieval house has an aisled hall that was open to the roof and featured a central open hearth. The fact it contains an aisled hall that has survived in its entirety gives this house significant historical importance. This single-bay aisled hall is more commonly found in earlier houses dating from the 13-14th centuries, rather than in the 15th century like this one.

There are some other unusual things in this house for example the cross-wing is located at the service end of the building which is strange as It is more common during this period to have the cross-wing at the solar end of the house. The cross-wing that stands today is not the original, but rather a replacement that was constructed in the 16th century.

The solar end of the house had been rebuilt but It was most likely a single-end bay with an upper floor, as shown in the reconstruction at the museum. It also could have originally been divided into two rooms that sat side by side. Unfortunately, there was no evidence when the building was dismantled to show that this was the case. Above the ground floor service rooms, there is another room.

Medieval House from Sole Street, Kent was reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1991, it was dismantled and erected for the second time in 2016.

Medieval House from Sole Street

Poplar Cottage from Washington

Poplar cottage was originally situated on a small plot of land on the outer edge of Washington Common in Sussex, it is thought to have been built between the 16th and 17th centuries. The common was an important resource during this period and was often used to pasture cows or gather fuel.

Poplar Cottage itself has two rooms on the ground floor, the first room is heated with a fireplace which is in a smoke bay (a type of chimney). The second room was most likely a service room and may have been referred to as the shop.

Cottages like this one were usually occupied by landless or nearly landless husbandmen, labourers, and craftsmen.

There are two rooms upstairs which were probably used as bedrooms.

Poplar Cottage from Washington, Sussex was dismantled in 1982 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1999.

Poplar Cottage from Washington common

Gonville Cottage from West Dean

Originally known as West Dean shepherd’s cottage, Gonville Cottage is the only building that was already at this location. It was built at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1848 and is now part of the museum’s collection. Gonville cottage is the home of the museum’s Historic Clothing Project, which features replica historical clothing that can be viewed, handled, and even tried on. Unfortunately, the cottage was closed during our visit.

Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen from Sundridge

Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen was originally located in Sundridge, Kent, and stood on the site of the Bough Beech Reservoir. It was donated to the Weald & Downland Living Museum by the East Surrey Water Company in 1967 to prevent it from being demolished. It was originally constructed in the early 16th century.

The Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen was the Museum’s very first exhibit building. It was re-erected in 1969 and was relocated to its current location near Bayleaf farmhouse in 2002. Evidence suggests Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen was part of a larger farmstead, rather than just a single farmhouse as was initially thought. This building lacks all of the typical construction methods that were associated with a traditional house of its time which is why it is displayed as a kitchen and not a house.

On the ground floor, there would have been two bays that came together to form a single space. One of the bays opened to the roof, indicating that a fire had been burning on an open hearth. The second bay had access to an upper room. Wood framing and wattle and daub construction were used to build the Tudor Kitchen and the roof is constructed in a crown post style; which is typical of the late-medieval period.

At some point, the house underwent renovations, including the addition of two doorways in the south wall, one of which led into the open bay and the other which provided access to stairs leading to the upper floor. The museum’s reconstruction of this building is based on these later modifications.

Winkhurst underwent additional renovations, at the west end, the adjoining structure was demolished and replaced with a timber-framed structure; which was still standing in 1967. A huge chimney stack was inserted into the western half of the open bay and a new opening for a staircase was created adjacent to the south gable wall.

It is thought the buildings adjoining the south and west sides of the Tudor kitchen were already in place when the kitchen was constructed, both have been reconstructed using modern methods to show what the building would have looked like in its entirety.

Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen from Sundridge, Kent was dismantled in 1968 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1969.

Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen

Cattle Sheds from Sussex

Cattle kept in yards were housed in open-fronted sheds, which provided them with shelter. Originally, each of these sheds was part of a farmyard group, which included barns and other sheds arranged around a foldyard. They were constructed in the late 18th or early 19th centuries.

Cattle were kept on traditional farms for a variety of reasons, including dairy products and meat. Cattle were kept in either cow-houses or foldyards which meant they could also produce manure that could be collected and used as fertiliser.

The yards were surrounded by walls or buildings, and the buildings were frequently open-fronted sheds where the cattle could take shelter from the elements. The sheds served as a place for the animals to rest and eat, and they were often equipped with feeding racks. In most cases, the animals were not tethered in the sheds so were free to come and go as they pleased.

The five open-fronted sheds re-erected at the Weald & Downland Living Museum are;

- Rusper – dismantled and re-erected in 1970

- Lurgashall – dismantled in 1970, and re-erected in 1971

- Kirdford – dismantled in 1971, and re-erected in 1973

- Coldwaltham – dismantled in 1973, and re-erected in 1974

- Goodwood – dismantled in 1986, and re-erected in 1988

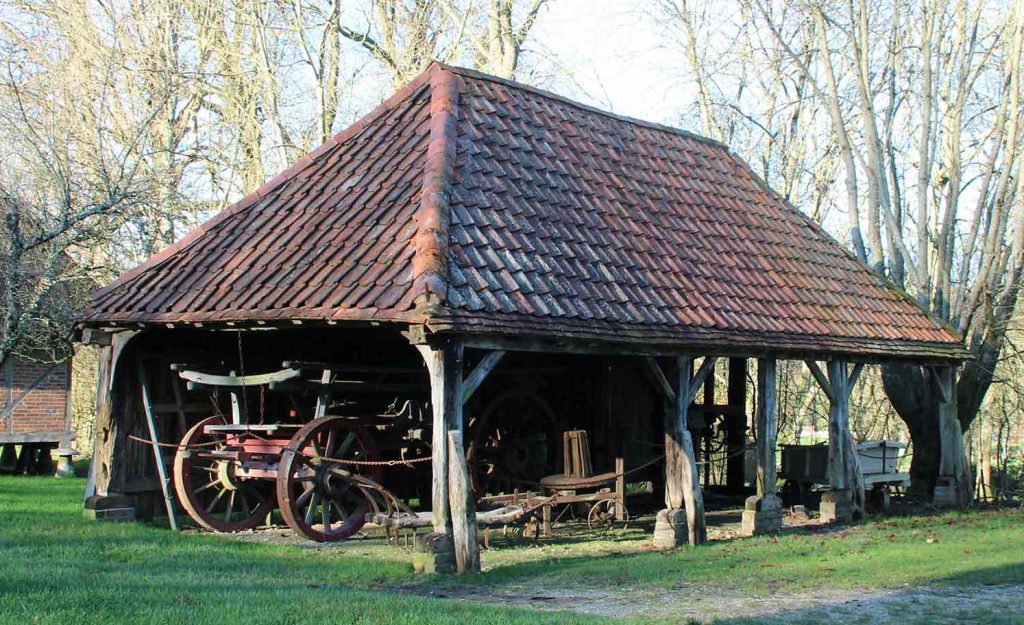

Wagon Shed from Wiston

This small wagon shed was constructed in the 18th century, and was originally located in Wiston, Sussex. It would have been built to store the carts and waggons that were used on the farmstead. Many wagon sheds were open-fronted structures that looked quite similar to cattle sheds, however, wagon sheds are slightly different because they face outwards from the yard rather than inwards. Wagon sheds are usually closed on one of both sides but open at both ends, allowing you to move carts in and out without having to reverse, however; this shed was built on a slope so is only accessible from one end.

The Wagon Shed from Wiston, Sussex was dismantled in 1976 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1980.

Wagon Shed from Wiston

May Day Farm Barn and Stable from Tonbridge

May Day Farm’s 18th-19th century three-bay threshing barn and two-bay stables formed part of a tenanted farm on the Summerhill Estate, just south of Tonbridge in Kent. A project to widen the A21 meant these buildings were destined for destruction. Weald & Downland Living Museum began dismantling the structures in 2015, and the timbers were stored at the Museum ready for re-erection the following year. The relocation project was partially funded by Balfour Beatty, which was the construction company that was in charge of the road widening.

The May Day Farm, Barn and Stable from Tonbridge, Kent were dismantled in 2015 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 2018.

May Day Farm, Barn and Stable from Tonbridge

Hay Barn from Ockley

This oak-framed hay barn was built in 1804 in Ockley, Surrey, and was originally part of a large farmstead. It was used to store hay under cover rather than in a stack outside the barn. It has a tiled and hipped roof which is supported by eight posts, and it is nearly square in shape. Four-foot deep weatherboard is fixed at the top of two opposing sides which allows air to circulate freely throughout the structure. The hay barn is currently home to a threshing drum, elevator, and living van that was used by the steam engine driver and his mate during the autumn wheat harvest.

The Hay Barn from Ockley, Surrey was dismantled in 1985 reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 2010.

hay barn from ockley

Barn from Cowfold

This barn with a timber frame was built around 1536. This structure’s primary function was to store and thresh arable crops such as wheat, oats, rye, and barley. It has a cattle yard on one side and a stackyard on the other.

The roof of the barn has a crown-post construction and the walls are weather-boarded for added protection from the elements. The timbers from the barn were analysed using tree-ring dating revealing that the trees used in the construction were felled in 1536, it is assumed the barn was built soon after. To create a typical late-medieval Wealden farmstead, Cowfold Barn has been situated near Bayleaf Farmhouse to form a farmstead.

The Barn from Cowfold, Horsham was dismantled in 1980 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1988.

Barn from Cowfold

Bayleaf Farmstead from Chiddingstone

Bayleaf Farmhouse was situated in Chiddingstone, Kent. It is a timber-framed house/hall and dates back to the early 15th century. It has six rooms, four on the ground floor and two upstairs.

In the centre of the building is a large hall that is heated by an open fire. On one end of the building are service rooms, to the left of the service rooms is a staircase that leads to an upper room.

On the other side of the house are the rooms the family would have lived in. There is a staircase within the room on the ground floor that has access to the upper floor. The upper room on the family side of the house is where the toilet is located.

The house is presented as it might have appeared around 1540, with replica furniture and equipment. The majority of Wealden houses were constructed in a single stage, but Bayleaf appears to have been constructed in two stages.

The open hall and the building’s service end were most likely connected to an earlier structure that stood where the solar end bay now stands.

The Bayleaf Farmstead from Chiddingstone, Kent was dismantled in 1968 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1972.

Bayleaf Farmstead from Chiddingstone

Hall House from Boarhunt

This Medieval Hall House is a small but well-built open hall house, it was built in the late 14th century and came from Boarhunt in Hampshire. This house has three rooms on the ground floor and an upper floor that was added sometime later. The upper floor is located above the main hall.

The hall has been built using a cruck construction. The term cruck refers to the long, curved timber that rises from the ground which helps to support the roof timbers. The cruck in this hall does not extend all the way up to the apex of the roof, because of this it is referred to as a base cruck.

Base cruck construction is rarely found in this type of building and is typically associated with aisled buildings from the Medieval period. The main hall also contains two hearths as well as a bake oven which is connected to a brick chimney. The chimney was most likely added at the same time as the upper floor. Unfortunately, many of the original timbers hadn’t survived when the house was rescued in 1970, so much of the design of this house is based on historical evidence and not entirely on the building that was left behind. It’s likely the bay to the right of the entrance was used as a service room. The service room was open to the roof, and the rafters and thatch battens had been heavily sooted from the original open fire.

The inner room, which is located beyond the hall, is a reconstruction of a typical mediaeval solar, which has been rebuilt using modern materials. The original solar end had been removed and replaced by a terrace of brick cottages, because of this, it is possible that the reconstruction of this section is not the correct size or shape of the original. In addition, the size and location of the entrance door and window openings in the hall are also unknown.

The Hall House from Boarhunt, Hampshire was dismantled in 1970 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1981.

Hall House from Boarhunt

Medieval Building from Hangleton

This reconstruction of a flint cottage is based on archaeological evidence discovered during an excavation of a deserted medieval village near Hangleton, in Sussex. It is believed that the cottage was constructed sometime during the 13th century.

The buildings at the excavation site were in such poor condition that it was impossible to reconstruct the cottage in its entirety based on what was left.

Evidence from two separate buildings at Hangleton was used in the reconstruction. The main room contains an oven and a hearth and has a layout that would have been typical during this period.

The roof construction and the type of wood used are all educated guesses based on what would have been available at the time of construction. However,

when the original cottage was built, wood shingles, turf, or other types of thatch such as broom or furze could have been used. Evidence showed that ceramic tiles, small Horsham Stone slates, and natural slates were used to cover the roofs of some of the buildings in the Hangleton village.

The Medieval Building from Hangleton was excavated in 1952-1954 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1971.

Medieval Building from Hangleton

Anglo Saxon Hall House

Like the Medieval Building from Hangleton, the Anglo-Saxon hall house is a reconstruction using archaeological evidence dating back to 950 AD.

The archaeology for this building was discovered at a site in Steyning in West Sussex during an excavation in 1988 and 1989.

The Saxon hall house has a wattle and daub construction and it was built using methods that would have been available during this period. The roof has been thatched with straw that was grown at the Museum.

The Anglo Saxon Hall House was excavated in 1988-1989 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 2015-2016.

Anglo Saxon Hall House

Downland Gridshell

The Gridshell is a lightweight oak lath structure. It was the first timber gridshell structure to be built in the Uk and is home to the Museum’s collections of tools and artefacts from rural life in the Weald and Downland region.

Its large interior makes it the ideal space for training, workshops and the construction of large scale conservation projects.

The construction of the gridshell at Weald & Downland Living Museum was started in 2000 and completed in 2002.

Downland Gridshell

Treadwheel from Catherington

This treadwheel was constructed sometime in the latter part of the 17th century. The well and the small house that was attached to it were relocated from a farm in Catherington, north of Portsmouth. The small timber building was situated over a 300ft deep well between the main house and a collection of barns. Water would have been retrieved from the well using a bucket attached to the treadwheel which would have required a person to walk on it. It is estimated that to bring the bucket up from the bottom of the well, the person walking on the wheel would have to walk a distance equivalent to a third of a mile.

Fun fact: There is a story of a young boy who was said to have slipped on a wheel similar to this one. He was said to have fallen just as the bucket was about to reach the top. The weight of the bucket caused the wheel to spin in the opposite direction, whirling him around and around until the bucket reached the water.

The building that houses the wheel is a timber-framed structure with a thatched roof. The original timbers showed no signs of daub; this type of structure was frequently constructed without it, which is why it has been reconstructed as it is. The Catherington wheel’s bucket is a reconstruction based on a bucket that still exists at Saddlescombe Manor near Brighton. A 19th-century galvanised well bucket is also on display, which was used at Catherington until about 1910 when the wheel became obsolete.

The Treadwheel from Catherington was dismantled in 1969 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1970.

Treadwheel from Catherington

Longport Farmhouse from Newington

The Longport farmhouse was constructed between 1500 and 1900 and is a typical example of a farmhouse that would have been built in Kent during this period. The site where the farmhouse was originally located was needed for the construction of the Eurotunnel terminal police station. Permission was granted to remove it on the condition that it be moved to another location and not demolished. The farmhouse served as the Museum’s entrance, shop, and offices until the new visitor centre was constructed.

The Longport farmhouse from Newington was dismantled in 1992 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1995.

Longport Farmhouse from Newington

Aisled barn from Hambrook

The aisled barn from Hambrook is a three-bay barn and was constructed around the mid-18th century. It is a typical example of the types of barns that were built in West Sussex and eastern Hampshire during this period.

The framework of the barn was constructed using oak. Reed was used to construct the thatch roof and Elm was used for the exterior boards.

The barn now houses the family activity hub where you can dress up. There is also a gypsy caravan for you to explore and traditional games to play.

The Aisled barn from Hambrook was dismantled in 1971 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1973.

Aisled barn from Hambrook

Pugmill House from Redford

The Pugmill House was located in Redford, Sussex it was constructed in the 19th century to house a pugmill that would have been powered by a horse. A pugmill was used to prepare clay to manufacture bricks and would have been part of a series of buildings including, brick drying sheds and a horse gin or engine.

The pugmill house is a brick and stone six-sided structure. It has two small windows on two of the walls, two large openings on two of the other walls, and two doorways on the other two walls. The inner walking circle measures 17 feet which is ample room for a horse.

The actual pugmill is an upright barrel that is open at the top and contains blades that are attached to a vertical shaft. The shaft is turned by a horse, or sometimes by wind or water power. The clay comes out of the bottom of the barrel in the form of a smooth paste that is easy to work with. The term “grinding” is used to describe this process, even though there is no actual grinding involved. Unfortunately, the pugmill at Redford didn’t survive; the one installed came from an East Grinstead brickyard.

The Pugmill House from Redford was dismantled in 1979 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1980.

Pugmill House from Redford

Brick drying shed from Petersfield

The brick drying shed was constructed in 1733, and its original location was at the Causeway Brickworks, which was located close to Petersfield. The brickworks were shut down during the Second World War, the glow coming from the open-top kiln would have been an obvious landmark for enemy aircraft.

The primary function of the brick drying shed was to protect newly moulded bricks while they were drying out. newly made bricks are prone to cracking if they dry too quickly, so movable wooden screens were used to shield the bricks from the wind and sun. The drying process can take anywhere from three to six weeks, and once it is complete, the bricks are put into a kiln to be fired.

The Brick drying shed from Petersfield was dismantled in 1979 and reconstructed at Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1988.

Brick drying shed from Petersfield

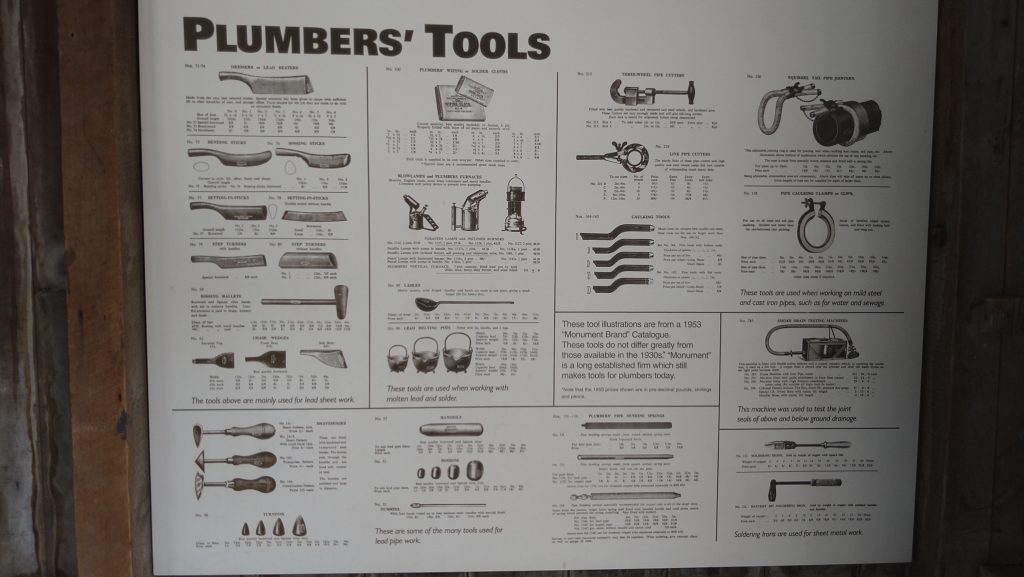

Plumber’s workshop from Newick

This Plumber’s workshop from Newick, Sussex dates from around 1817. The workshop itself originally formed part of W R Fuller, Plumbers and Decorators which was established in 1792.

W R Fuller, Plumbers and Decorators moved its operations in 1817 to the Burnt House in Newick, and then again to the Red Brick House in 1888; It was probably around this time that the workshop was constructed. The workshop was one of three buildings, which included a painter’s shop and a shop/showroom. The other two structures were demolished in the 70s.

The ground floor of the building originally contained the plumber’s workshop, and the first floor contained the glazier’s workshop. The ground floor has been laid out to represent the plumber’s workshop.

The Plumber’s workshop is a typical example of the construction methods that were used during this period, it would have been fabricated in various sections and assembled on-site using bolts

The Plumber’s workshop from Newick was relocated in its entirety to the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1985.

Plumber’s workshop from Newick

Whittakers cottages from Ashtead

Whittaker’s cottages were built around the mid-1860s in Ashtead in Surrey. One of the cottages has been furnished to reflect the style of the late 19th century and the other has been left unfinished exposing the timber-framed structure.

The cottages are 12ft wide and 20ft long with a total of four rooms, (two on each floor). The ground floor front room doubled as a living room and kitchen. As the living room contained the only fireplace on the property this is also where food would have been cooked.

The backroom would have been used for food storage and food preparation and the upstairs rooms were used as bedrooms. There would have been a storage shed and a privy located at the back of each cottage. Here are the specifications for a cottage of this period.

The Whittaker Cottages were named after an elderly agricultural labourer named Richard Whittaker. Whittaker sold a one-acre paddock to the railway company in 1849 when they were building a line from London to Portsmouth.

Ten years later the railway line opened, but it only occupied a strip of land down the middle of the paddock. The remaining land was sold to a baker by the name of F Felton, who built the cottages and rented them out to agricultural labourers.

The Whittaker cottages from Ashtead were dismantled in 1968 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 1997.

Whittakers cottages from Ashtead

Bell Frame from Stoughton

This bell frame was given to the museum by St. Mary’s church in Stoughton, West Sussex, when a new bell frame was added. It dates back to the late 16th or early 17th century.

The shingled spire was installed on the bell frame in 2009, the purpose of this was to demonstrate the most effective method for applying hand-cleft oak shingles.

The Bell Frame from Stoughton was donated to the museum and the shingled spire was constructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 2009.

Bell Frame from Stoughton

Church from south Wonston

This church also known as a tin tabernacle or iron church was constructed in 1908 so that residents of South Wonston would have a place of worship. The building is approximately 30ft long and 15ft wide and has a vestry and a little porch.

The church bell is housed in a small roof extension at the east end of the building and is rung using a pulley that is located in the vestry.

The hymn board, candle stand, altar, and altar cloth are all original to the church; the other furnishings were either purchased, given as donations, or crafted at the Museum.

The Church from south Wonston was dismantled in 2006 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 2011.

Church from south Wonston

Horse whim and open shed from West Kingsdown

This three-bay structure dates back to the 19th century and was originally located in West Kingsdown in Kent. This structure also contains a cart shed which is open on all four sides, suggesting that it may have served as a wagon or cart shelter in the past. Saw cuts on the tie beams, on the other hand, suggest that it was also used as a saw shed, and the baulk to be sawn was placed on the tie beams rather than on trestles or over a pit.

This open shed houses a horse whim which was used to raise water from the well beneath. The horse whim was operated by a small horse or pony. There is a pin located in the main shaft that when removed or added, allows the drum to either move freely or lock into a position to allow you to lower or raise the bucket attached, the speed of the descending bucket is controlled using a brake.

The Horse whim and open shed from West Kingsdown was dismantled in 1981 and reconstructed at the Weald & Downland Living Museum in 2000.

Horse whim and open shed from West Kingsdown

You may also like

Cosmeston Medieval Village

Cosmeston Medieval Village is nestled in the picturesque Vale of Glamorgan in Wales. This remarkable archaeological site offers a unique window into the past, giving you a glimpse of what life would have been like during the 14th century. Through meticulous…

The Sherlock Holmes Museum

The Sherlock Holmes Museum is a quirky recreation of the world of London’s most iconic fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes. Here, you can immerse yourself in the Victorian world of Holmes and some of his most famous cases. The best part? This museum is actually…

A Day At Butser Ancient Farm

Butser Ancient Farm is a non-profit community interest organisation dedicated to the study of ancient history. It was established for educational and research purposes, and it is open to the general public on weekends and Hampshire school holidays. You will see…