Butser Ancient Farm is a non-profit community interest organisation dedicated to the study of ancient history. It was established for educational and research purposes, and it is open to the general public on weekends and Hampshire school holidays.

You will see reconstructed buildings represented at this location from each of the historical periods including;

- Stone Age

- Bronze Age

- Iron Age

- Roman Villa

- Anglo-Saxon Longhouse/Hall

The construction of the buildings at Butser Ancient Farm is based purely on evidence gathered from archaeological excavations that were carried out at various locations throughout the UK. The evidence gathered during these excavations is used to test theories about what technology was available at the time, and what building techniques would have been used during the construction of their homes. This experimental archaeology is allowing archaeologists to gain a better understanding of the past and how our ancestors would have lived.

What to expect from our article

- 1 Experimental archaeology

- 2 Welcome to the Stone age

- 3 Mesolithic shelters

- 4 Durrington 851 late neolithic house

- 5 Horton house

- 6 Building boats

- 7 Welcome to the Bronze age

- 8 Welcome to the Iron age

- 9 Moel y Gerddi

- 10 Danebury CS1 Roundhouse

- 11 Danebury hill fort, CS14

- 12 Little Woodbury roundhouse

- 13 Toilet

- 14 The granary

- 15 Herb garden

- 16 Thatch roof construction

- 17 Other experiments that were carried out in the iron age section

- 18 Welcome to the Roman period

- 19 Roman villa

- 20 Welcome to the Saxon period

- 21 Charlton longhouse a2 (the first reconstruction)

- 22 Workshop

- 23 Animals

- 24 Herigeas Hundas

Experimental archaeology

Butser Ancient Farm is an entirely experimental archaeology site which means the buildings here will change over time, and some may even disappear altogether. Everything built on the farm is done so to help archaeologists learn more about the past. This information helps them to get a better understanding of how they lived and the different building techniques they would have used.

Don’t be disappointed if you see something in our article has disappeared from the site. It just means they have learnt all they need to know about the project and something brand new and exciting will be arriving in its place. If you want to support the ongoing historical experiments at Butser ancient farm you can make a monthly donation of £5.99 with Butser Plus. Your Butser plus donation will give you access to all the behind the scenes videos that tell the story of Butser Ancient Farm.

Welcome to the Stone age

The stone age section of Butser Ancient Farm has a total of five dwellings, two shelters, two small huts and the larger Horton House. The dwellings in this section represent the periods of the stone age.

- Palaeolithic – one million to 10,000 BC

- Mesolithic – 10,000 to 4,200 BC

- Neolithic – 4,200 to 2,500 BC

Mesolithic shelters

In this section, two Mesolithic shelters can be found.

Mesolithic people were hunters so they would have followed animal migration patterns to ensure they had a constant food source. Their shelters were intended to be only temporary structures, however, evidence shows that some people from this period did set up permanent homes near places where food was plentiful.

The shelters in this period are constructed using branches, brushwood, animal skins, hides, bracken, heather and reeds.

As you will see throughout this article over time the people of ancient times began to settle down and these temporary shelters evolved into better, more permanent structures.

Durrington 851 late neolithic house

There are two smaller huts as you enter this section, each of them represents the Palaeolithic period.

Archaeology for the Durrington 851 reconstruction was found during excavations in 2005 at Durrington halls near Stonehenge.

The roof of the huts is made with thatched wheat straw and the second house was more of a spiral as you can see in the photo. The curved shape of these dwellings meant they were stronger and more durable when exposed to high winds and stormy conditions.

Evidence showed a fence separating these two houses from the other houses found at Durrington halls, the same evidence showed it would have had a dresser and box beds. There was an oval central fire which was set in a square plaster floor.

Both of these houses were constructed using the wattle and daub method. Wattle and daub is a building technique that has been around for thousands of years. Walls would be built using vertical wooden stakes known as wattles, twigs or branches were horizontally woven between the vertical stakes then covered with daub. Daub is a cement-like product which can be made using wet soil, clay, sand, animal poo and straw.

It may seem like these two dwellings are in a state of disrepair; however, they are actually under investigation. Allowing the huts to deteriorate means archaeologists can gather even more evidence to further their research. The experimental archaeology at Butser Ancient Farm is important because it allows researchers to gain a better understanding of how ancient people lived, as well as how their homes fared over time.

All the information gathered during one build is used to help with the next one, for instance, one of the houses at butser Ancient farm had a little too much thatch on the roof which meant smoke from the fire accumulated inside the house instead of filtering through the thatch. It’s quite fascinating when you think about it as ancient people must have worked in the same way learning from each of the builds as they went, meaning researchers are quite literally walking in the footsteps of our ancestors.

Horton house

The third dwelling in the stone age section is the much larger neolithic Horton House.

Horton House is a reconstruction of a Neolithic building and its construction required a whopping seven tons of Scots pine and six tons of thatch.

Horton House was constructed based on evidence discovered by Wessex Archaeology at Kingsmead Quarry near Horton in Berkshire. The original house is thought to have been constructed around 3800-3600 BC.

There were a total of four structures discovered on the site at Kingsmead Quarry, with Horton House being the largest, it was said to be an exciting discovery as there is very little evidence left of Neolithic housing in the UK.

Building boats

A series of experiments were carried out at Butser Ancient Farm to gain a better understanding of the construction of boats. To hollow out the boats, they used a combination of burning techniques as well as using prehistoric tools made of wood, shell, antler, and bronze. A total of two boats were constructed for the experiment: one from an oak log that had been felled by a storm in 1984, and the other from an easier-to-work scots pine that had been felled a month or two before the experiment began. They discovered the older tree worked best using the burning technique as the newer one hadn’t dried out enough.

Welcome to the Bronze age

The Dunch Hill Round House is located in the bronze age section of Butser Ancient Farm. It has a slightly irregular circular ground plan, with ten post holes, and an eleventh post hole which is slightly off centre.

For the reconstruction of this roundhouse, archaeologists used oak for the post and lintel frame, as well as alder and pine for the rafters. hazel battens were used to attach approximately one ton of water reed thatch for the roof.

Several organisations worked together to bring this roundhouse to life, including Step Together Volunteering, with assistance from Breaking Ground Heritage, and Operation Nightingale. Operation Nightingale is a recovery initiative that assists wounded and injured veterans by involving them in archaeology to help aid in their recovery. The roundhouse was built almost entirely by 33 volunteers from Operation Nightingale.

You may have noticed that there is an unusual mix and match of walls on display in this house, as we know natural materials don’t hold up well over time. Unfortunately, there is no archaeological trace of what materials would have been used to finish the walls so the different types of wall materials you see in this dwelling are the result of experimentation. Archaeologists will keep an eye on each of them to figure out what was most likely to be used to construct the walls and how well each one holds up.

As you walk through the front door, from left to right, you will see;

- A turf wall up against a hazel wattle

- A turf wall against a split hazel wattle

- Earth against the split hazel wattle

- Earth against a wattle panel with a daubed interior. A gap has been left at the top to test for ventilation

- Earth against a wattle panel with a daubed interior

- A gabion wall with a double-sided wattle panel that has been daubed on both sides and filled with flints at the base to act as a damp course and stuffed with wool

- Chalk cob/clunch wall, made from a mixture of chalk, hair, and straw

- Build a chalk cob/clunch wall with a gap at the top to test ventilation

Welcome to the Iron age

Moel y Gerddi

Moel y Gerddi roundhouse is based on one that was discovered near Harlech, North Wales, it is quite unique because it had two entrances. This house is referred to as a two-ring roundhouse because it has an inner ring of twelve posts. The ring was built with ash posts, and the walls were built with approximately 700 three-metre-long hazel rods. It was built with wattle and daub construction, with the daub consisting of a mixture of clay, dung, soil, and fibre.

It is approximately ten metres in diameter with a basket cone roof. The roof was constructed of Scots pine and hazel, and it was thatched with 2.5 tons of long straw, which took approximately three months to complete. As we already mentioned the original reconstruction of this house included a second door that was filled in when the building was converted from wattle and daub to stone construction.

Following the completion of the Moel y Gerddi roundhouse, it was decided that the interior should be decorated and furnished in order to give visitors an idea of how this house might have appeared during ancient times. This was done in the style and method of the middle to late Iron Age. In addition to the hearth area, this house features A bed, storage chests, dressers, looms, and a kitchenette.

The interior walls were painted with lime wash to make the space appear lighter, with patterns based on the Waldalgesheim scroll style, which dates back to the third-fourth centuries were painted on the walls.

To achieve all of the colours used on the walls pigments were mixed into the lime wash;

- Red was made with iron oxide derived from Hengistbury Head iron ore,

- Yellow was made with ochre from Somerset

- Black was made with charcoal

It was discovered in 2009 that the inner posts in the Moel y Gerddi roundhouse were rotting. An experiment was carried out to determine whether it would be possible to replace all of the posts without having to completely demolish the structure itself. The experiment was a success, and all twelve internal posts were replaced as a result.

Danebury CS1 Roundhouse

The Danebury Roundhouse is based on an excavation of a roundhouse at Danebury Hill Fort, which is located just south of Andover, Hampshire.

Excavations revealed slot trenches showing that the structure’s walls were made of wooden planks rather than the more common wattle and daub method. It was for this reason that the house was chosen for reconstruction at Butser Ancient Farm.

The walls of this reconstructed house are made using approximately sixty oak planks, which are all joined together using hand-forged iron nails. layered in between the oak planks is sheep fleece, it is placed there to help to provide additional warmth and protection from the elements.

Evidence found during excavations showed a double set of post holes in the doorway of this house, which suggested that it may have had sliding doors. Several methods were experimented with to recreate the sliding doors, but it was determined that they were not really practical, and were switched out for the current ones. The current doors are supported by vertical poles, which makes them more stable and easier to open than the sliding doors would have been.

Danebury hill fort, CS14

When the Danebury hill fort cs14 reconstruction project was started, the goal was to learn more about the engineering of standard late-iron-age houses. According to the excavation reports, Danebury Hill Fort, CS14 was one of the best-preserved examples on the site, and it was chosen for reconstruction because it would be a more accurate representation of the original.

Research showed the vast majority of the houses on the site were constructed using stakes with a diameter of approximately 20-30cm. Only a small number of houses used the wattle and post method.

Danebury hill fort cs14 is a circular design with a 7.3m diameter. The construction of the walls for this house used A total of 140 rods which were spaced 120mm apart. A number of small rods were secured horizontally at the tops of the stakes around the perimeter of the house to provide it with additional support and strength. Willow was chosen for the wattle as it was found to be more durable and more flexible than hazel. the roof was constructed using birch and hazel and it was thatched with wheat straw.

The evidence found during excavations for this house showed there was a small wattled fence on either side of the doorway on the outside of the house. The same evidence indicated that there were two ovens inside the house, both of which were close to the fireplace. One of the ovens was equipped with an internal perforated shelf.

During the Danebury excavations, archaeologists found an intact piece of daub, complete with red paint on the surface. It was for this reason that the outside walls of CS14 were painted red. This was achieved by mixing coloured pigments into the limewash. Red is achieved by roasting an iron ore to make ochre.

Little Woodbury roundhouse

Little Woodbury, a wattle and daub roundhouse, was inspired by an archaeological excavation conducted at Little Woodbury, which is located near Salisbury. This is one of the largest roundhouses at Butser Ancient Farm. It is 14.5 metres wide, its roof is made from a whopping 7 tons of thatch, the frame and walls of this structure were made using 12 tons of oak, and the rafters were made of ash and elder weighing another 4 tons. When you think about what went into this reconstruction it’s actually a very impressive build.

During the deconstruction of a previous house at Butser, it was discovered that charring the ends of all of the main timbers before setting them into their post holes would help to slow or prevent the decay of the timber below ground level. This method was used in the construction of Little Woodbury.

Toilet

In an iron age settlement, it is likely they would have had a communal toilet, which would have consisted of a seat above a hole in the ground. Evidence also suggests that there could have been individual toilets for each house that was surrounded by a shelter for privacy like the one in our picture. Once a toilet was filled it would be buried and another hole would be dug next to it.

These days we have the luxury of toilet paper but during ancient times, it is likely they would have used things like moss, hay or even leaves as a substitute. Can you imagine how stinky these toilets probably were?

According to archaeologists, they can pinpoint the exact location of a toilet at a settlement as It appears that several locations throughout the camp have higher soil quality than others. This suggests that human waste has fertilised the soil there.

The granary

This was where the grain for human consumption was kept. Granulated grain served a variety of functions and was used to make items such as bread, porridge, and beer. Rats and mice were unable to climb into the granary because of the flat discs above the legs.

Herb garden

The iron age herb garden contains a variety of herbs that people would have been using during ancient times. evidence shows that herbs were grown primarily in the vicinity of human settlements, and would have been used for ceremonial and medicinal purposes. A lot of these herbs are still in use today, but they are mostly used as ingredients in recipes rather than in medicine.

Thatch roof construction

You may have noticed that there aren’t holes in the roof to allow the smoke to escape from the buildings, having a hole in the roof can be more dangerous than not having one at all, here’s why; A hole can result in a through draught, which can increase the intensity of a burning fire allowing more oxygen to enter.

Without a hole, the oxygen levels at the very top of the house are relatively low, which means that any embers that fly up from the fire are extinguished before they have a chance to catch fire. A hole, on the other hand, increases the likelihood that embers floating upward will remain alight and ignite the thatch surrounding it.

The fact that there is no hole in the roof has an additional advantage, smoke from the fire will fill the top of the roof while slowly filtering through the thatch, As a result, the smoke will kill any insects or small animals hiding in the thatch, which also decreases the likelihood that birds will break open the thatch to get at them.

Other experiments that were carried out in the iron age section

Clunch house

Clunch is a type of Iron Age concrete that is made from crushed chalk, mud, water, and straw, and it has been in use since the Middle Ages. The clunch house served a variety of functions, including storing items used in the production of clunch, such as straw, hay, and tools.

Storage pits

Harvested grains were stored in deep pits with clay lids to keep them protected from the elements until the following year’s planting. From the research and experimentation carried out at Butser Ancient Farm, it has been discovered that grain can be stored in this way for over a year and the grain will still germinate when it is planted.

Hayrick

Hay was an essential source of nutrients for farm animals during the winter months, so it was stored in a hayrick to keep it fresh. Using a thatch roof, the hay could be kept dry and protected from the elements.

Welcome to the Roman period

Roman villa

The Roman villa at Butser Ancient Farm is based on excavations at Sparsholt, near Winchester. It gives you an understanding of how differently the Romans might have lived in comparison to the regular people of the roundhouses. This particular villa was part of a farmstead which included a bathhouse and a barn. It is not clear how the rooms in the Roman villa were used, but current research and experiments suggest that they would have been similar to the ones laid out at Butsers Roman villa.

A Roman villa has a far more homely and luxurious feel to it. It would have been bright, airy and exquisitely decorated, however, when we compare the practicalities of the Roman villa to the dark and smoky roundhouses of the Iron Age, the roundhouse would most likely win. Yes, the villa looks nicer with its glass windows, tiled roof, and beautifully decorated interior, but research suggests it would have been significantly colder than the roundhouses.

A Roman villa is heated primarily with a hypocaust, much like the fire inside a roundhouse, however, the hypocaust was situated outside the villa. It was connected to a series of tunnels that ran beneath the floor and In order to provide constant heat to the villa, you would need to keep a fire going at all times. When the hypocaust was lit, the heat would travel through the tunnel system, and up through flues in the walls keeping the villa warm.

It is not known why but this villa only had one heated floor, the other rooms would most likely have been heated with a brazier which was a popular feature in a Roman villa. Braziers are upright metal bowls which are filled with charcoal. Braziers were a multi-purpose item, they were used to heat a room and also for cooking food.

This villa comes complete with two toilets this one is a wooden reproduction of one found in Rome at the Caracalla Roman baths c. 215 C.E

The other one is a communal toilet which is situated at the back of the property.

No Roman villa would be complete without mosaic flooring, and this particular example does not fail to impress. To create this floor it took a total of 1000 hours and approximately 120,000 tesserae. Tesserae are the small coloured stone cubes that were used to create mosaics during Roman times. It would have taken a great deal of skill and patience to construct a typical Roman floor from start to finish. This mosaic floor is a replica of the one found at Sparsholt villa, if you want to see the original it is on display at Winchester museum.

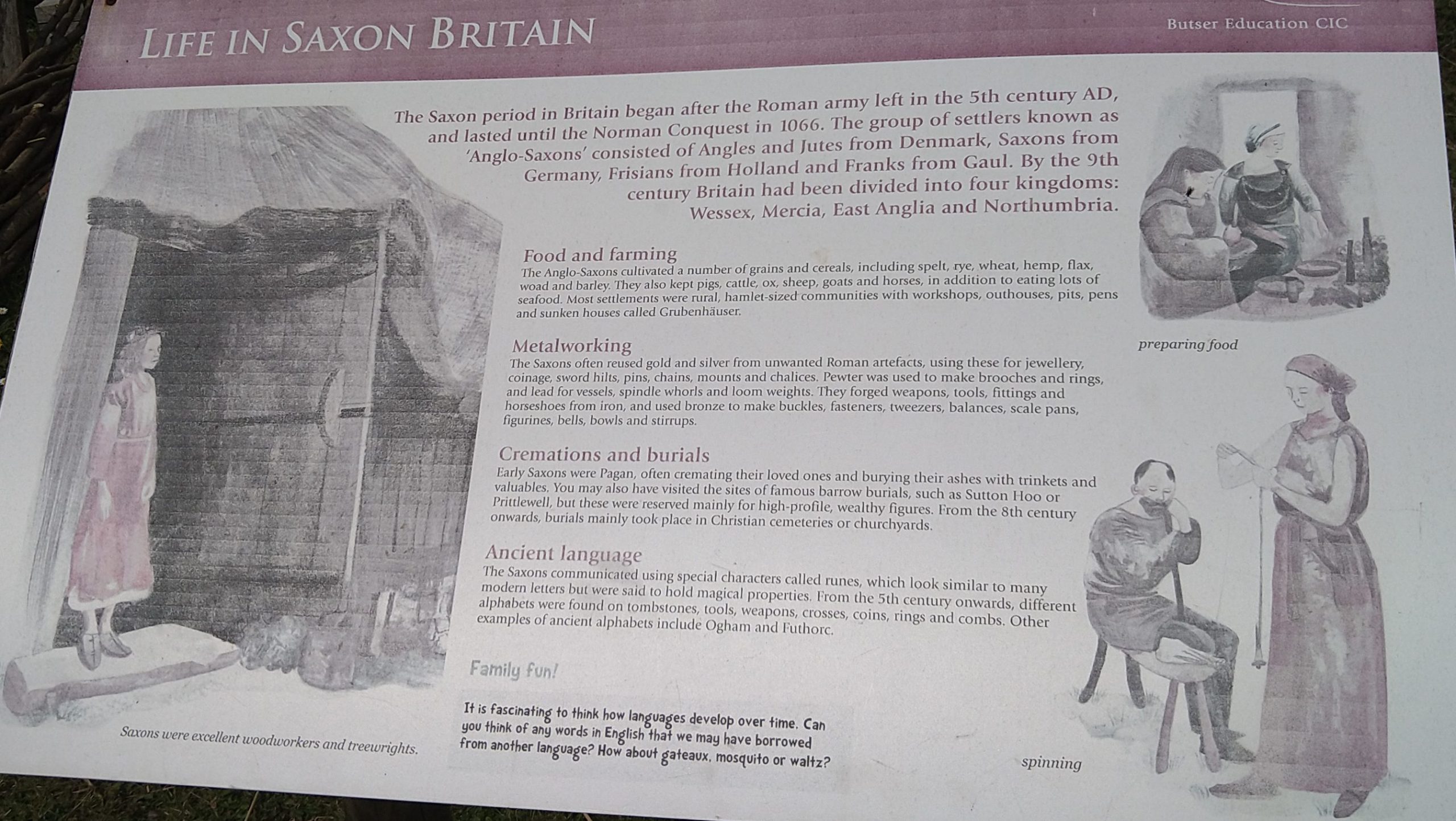

Welcome to the Saxon period

The withdrawal of the Roman army from Britain during the fifth century AD marked the beginning of the Saxon period. Excavations at the village of Charlton, in the early 1970s, revealed an Anglo-Saxon settlement.

In May 2015 work began at butser Ancient Farm on a reconstruction of the Charlton Saxon longhouse, a second (on the right) was added more recently.

Charlton longhouse a2 (the first reconstruction)

The timber used in the Charlton longhouse reconstruction was oak, sweet chestnut and hazel. The walls are made of wattle and daub and the roof is made with wattle hurdles, (weaved panelling that was popular for fencing during this period).

This particular thatch roof was made of wheat straw and is held in place using hazel spars. Spars are flexible strips of wood with pointed ends.

There were no nails and screws during this period so wooden pins and dovetail joints were used to hold it all together.

Fun fact!

If you want to know where the word window comes from, look out for the triangular hole (wind eye) at the entrance of this longhouse. It was placed there to allow friendly spirits to enter, wind eye would later become window.

Workshop

Butser Ancient Farm is primarily an education and research site with a working workshop area teaching you the way of our ancestors. There are many workshops at Butser, from metalwork to spinning and weaving. See the full calendar here

Animals

Butser Ancient Farm is home to a variety of rare breed animals, including Manx Loaghtan Sheep and English Goats, as well as pigs during the summer months. If you want to get up close and personal with the sheep and goats, you can purchase a bag of animal food from the visitor centre.

If you want to get a real up-close and personal sense of the past and what life would have been like during ancient times I highly recommend visiting during an event day. Butser Ancient Farm hosts a variety of special events and workshops throughout the year, such as storytelling sessions, Celtic festivals, concerts, and historical re-enactments all of which bring the past to life. We were lucky to visit on a day that Herigeas hundas were at butser and we thoroughly enjoyed the whole experience.

Herigeas Hundas

Herigeas Hundas is a group of experienced battle reenactors based in Hampshire, England. They portray Anglo-Saxons from the late 4th to the early 7th centuries. The group has a wealth of experience with cavalry and siege weapons, carrying out historical battle reenactments at various locations throughout the Uk, including Butser Ancient Farm.

Herigeas Hundas put a huge amount of effort into full-contact combat reenactments using a variety of weapons giving visitors a fully immersive and entertaining experience.

Don’t be fooled by the tough exterior as Herigeas Hundas are more than just battles and fighting; each of their members brings something unique to the group, from blacksmiths, woodworkers, and leather workers to warriors and seamstresses, all of whom create everyday essentials using traditional Saxon methods and tools. To learn more about the Herigeas Hundas Reenactment group read the full article here.